Caregivers in 50 countries ask for recognition of unpaid labour

Story by Leila Hawkins

Photo by Kelly Sikkema, creative license

A landmark report that gathers the views of mothers and caregivers from 50 countries has found that caregiving work comes in many forms that are largely unrecognised.

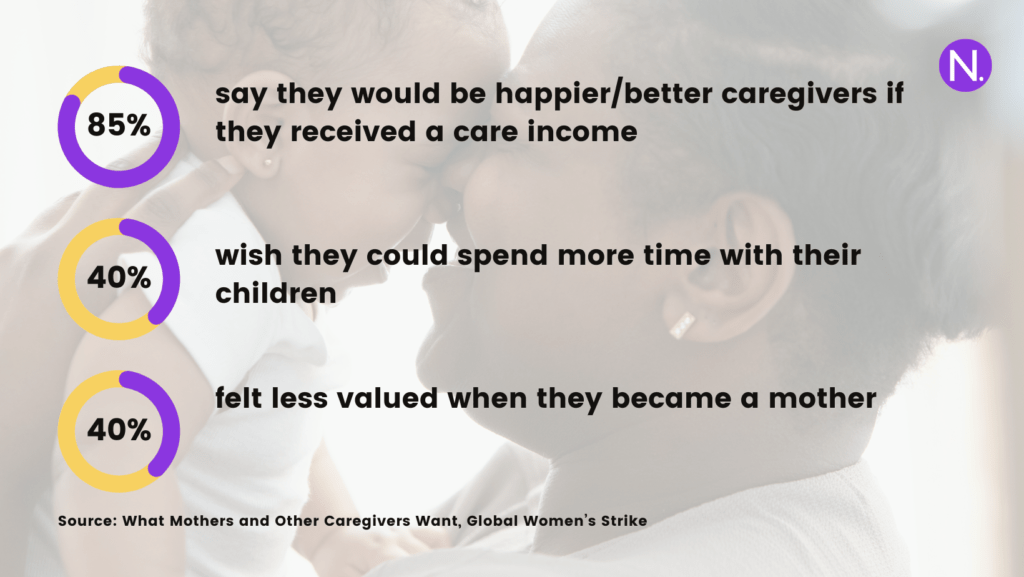

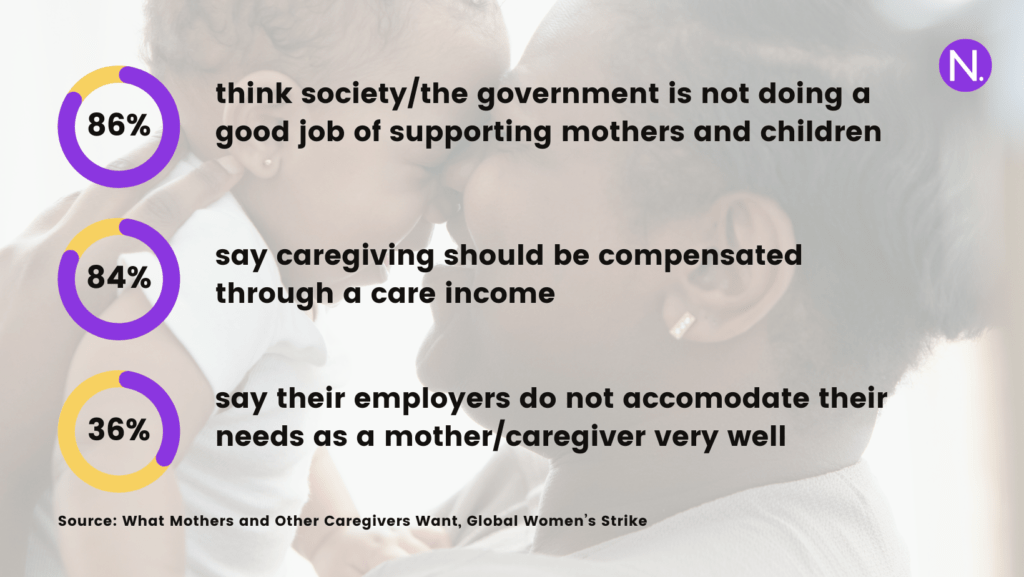

A key finding is that 84% of respondents consider their caregiving to be a valuable contribution to society that should be paid through a “care income”. This raises the point that caregiving, while unwaged and not recognised by conventional labour metrics, is essential work, but is often invisible.

The report collects the findings of a survey created by Global Women’s Strike (GWS), who put together a working group of people based in Thailand, the UK and the US to create and distribute the questionnaire. Designed for caregivers from different racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds and made available in several languages, it took a year to produce, as the group tested it to ensure the language was inclusive and made as much sense to domestic workers in Peru as it would to mothers in the US.

The survey officially launched on March 8, 2022, coinciding with International Women’s Day and the 50th anniversary of the International Wages for Housework campaign, which coordinates GWS. It was then shared on social media and distributed at street stalls, schools and community events.

As a result, it is a hugely comprehensive piece of research that shows that around the world, the work of caring for children, the disabled and the elderly, needs to be valued and compensated far more than is currently the case.

“Caring work is essential to the whole of society yet we are impoverished for doing this work. Can you think of anything more unjust?”

More than half the respondents said they are solely responsible for raising their children, with the majority spending more than 40 hours a week on caregiving.

Activities including breastfeeding and helping with homework were identified as care work, as well as defending loved ones from racism, discrimination and violence, and caring for the natural environment.

“Like caring for our fellow human beings, caring for the land and for the natural world is similarly hidden and unvalued,” one respondent said. “Many of us are involved in many things for the environment, for the Amazon, so we are glad care work is extending to our natural world as well as people.”

The double duties of caregivers

While 63% of respondents said they have a paid job out of financial necessity, 71% said they would not work the same job or hours if it weren’t for financial pressures. Only 5% would choose to work full-time outside the home if they had no financial constraints, and most would prefer more time with family and part-time paid work. “There is no recognition for women who do a double day… I would work part time or not do waged work outside the home if I could,” said one response.

Working mothers also said that their waged job did not provide breastfeeding breaks in 33% of cases, while 34% said their job did not provide family or medical leave to take care of a newborn or someone who is sick.

The report also draws attention to the fact that maternity leave varies widely around the world, from 14 weeks in Thailand to 68 weeks shared by mothers and fathers in Sweden. The US, one of the wealthiest nations in the world, has no statutory maternity leave. “I work for a big global corporation, but only got four weeks of paid maternity leave,” one respondent said. “I could take up to a year of unpaid maternity leave, but the time is taken from your seniority at the company. Maternity is penalised, but any other “disability” is covered.”

A respondent in the UK decried “practically non-existent” social care, calling for “radical reform” in funding and supporting caregivers. Others highlighted discrimination against single mothers and the need for constitutional protections.

Caregiving comes in many forms

Most people surveyed wanted to care for dependents like elderly relatives at home, especially in Thailand and Myanmar, where caring for loved ones at home was the only option they would consider. “Cared for both parents until their death, and for my partner,” one respondent said. “States should recognise this as life-saving work. Instead we are invisible, unpaid, impoverished for doing it.”

Importantly, the survey encompasses the views of trans women in Latin America, mostly in Brazil but also Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia. Most are raising children, with some sharing responsibilities with close friends and chosen family. “We wish we could spend more time with our children,” said one testimony. This is made much harder when you are not only in poverty, but you are facing a lot of violence and discrimination. All of your energy and resources are spent on trying to remain alive.”

Respondents in Mexico explained that trans women in their communities have a particular caregiver role. “It is the same as the daughters who stay at home and care for the elderly parents and relatives and collectively for the children of others.

“Yes, the bond between mother and child is vital, but the bond with another primary carer or relative can sometimes be as important… Women that have raised us when our own mothers have abused and rejected us. We feel the bond and role of the mothers in our lives, and it is valid and important and should be respected, because these women have given us the love we never received in our biological families.”

One of the women said: “The government and society will never compensate us for our work because they don’t even want us alive, or any of the people we care for. And we are definitely not seen as mothers or caregivers as we are not even seen as women.”

The need for a care income

The majority of the respondents (85%) said they would be happier and better caregivers if they received recognition and financial support for their caregiving labour.

Mai Janta is part of GWS Thailand, the Community Women Human Rights Collective of women representing 19 different communities. “We are women caring for and defending the land, environment, and Indigenous peoples. We are women demanding justice for our livelihoods such as sex workers, factory workers, migrant workers, and street vendors. We are women from slum communities insisting on housing and an end to poverty. We are disabled women, single mums, and other women struggling for democracy. We are all caring for our families, communities, and society.

“When I thought about the work we do at home and the work we do outside the home, often the only difference is we only get money for the work we do away from our home and family. It got me thinking, why don’t we get paid? Why does a woman have to leave her home to care for someone else’s children simply to make enough money to care for her own kids and family?”

“Care income doesn’t take a lot of explanation for women who do the caring work unwaged everyday to understand and embrace it,” she added. “It is not a university theory; it is a grassroots common-sense solution.”

What caregivers need: a case for policy reform

Speaking at a webinar to launch the report’s findings, Dr Laura Connelly, Chair of the Sex Work Research Hub at the University of Sheffield, emphasised the importance of the research. “This report then provides a much needed body of evidence, painstakingly examined by the team, a body of evidence that demands attention. It should be taken seriously by policymakers and others in positions of power, by academics and by the public at large. It provides a compelling case for policy reform, and community support.

“Most of all, we hope that the report will become a resource for mothers and caregivers across the globe, amplifying their calls for recognition, support and a care income,” she added. “We hope that the findings of this report which embody this collective voice of caregivers are not just heard, but acted upon.”

During the webinar, Selma James, who co-founded International Wages for Housework in 1972, said: “I feel that the [care] income validates that what we do is central to reproducing the whole human race and making life on this planet what we want it to be.

“What people have said today we need vitally 10 times over and 10 times over that. So we know what people are going through, how people are managing to survive, what kind of a life any of us wants to live together, and we can build a fantastic movement to change the world for carers, and for all of us to be carers.”

READ MORE

3 thoughts on “Caregivers in 50 countries ask for recognition of unpaid labour”