What is feminism in 2024?

Written by Leila Hawkins

Street art and photo by Whatifier

It’s a confusing time to call yourself a feminist. Depending where you look at the moment, feminism is either Taylor Swift or Barbie; has gone too far; or is being erased by transgender people.

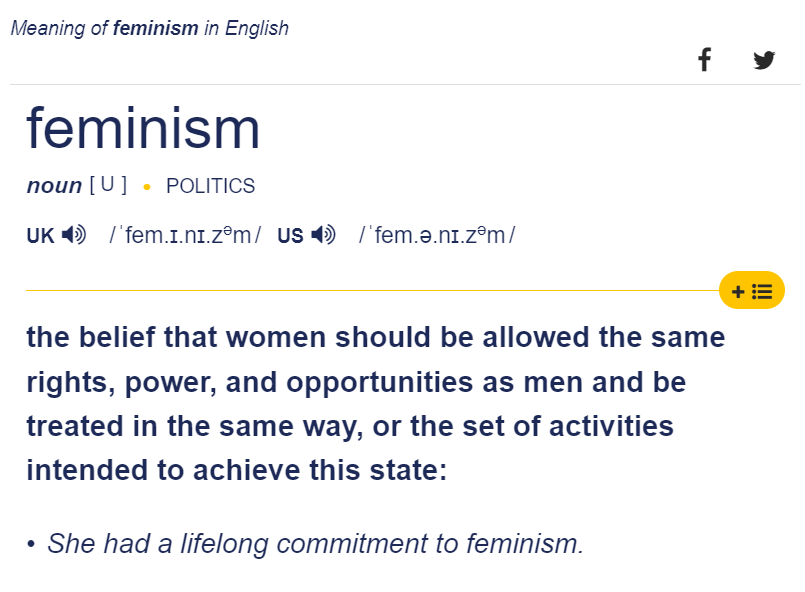

A 2023 YouGov survey revealed that when directly asked, less than half of the respondents (who were based in Western Europe and the US) said they identified as feminists. However when another group was asked the same question and given the dictionary definition of feminism — the belief that women should be allowed the same rights, power, and opportunities as men — between 45% and 77% of respondents in the various countries said they did, in fact, consider themselves to be feminists.

How did we get here?

Is Taylor Swift a feminist?

Type ‘Taylor Swift feminist’ into a search engine and you will find multiple articles, and even academic papers arguing that she is either the ultimate icon of female empowerment or a performative white feminist. Much like the subject matter of her songs, her stance on social and political issues has become a huge topic of debate.

Swift is an enormously successful American singer-songwriter. A recording artist since the age of 14, she became known for her highly relatable confessional lyrics describing relationship break-ups, but she has also tackled coming-of-age, self-love and female friendship.

Like many artists, the masters of Swift’s albums initially belonged to her record label, meaning that the label was able to sell these to whomever they wished (in this case to talent manager Scooter Braun), with the vast majority of the profits from sales going to the owner. After a series of disagreements and claims of Braun’s alleged bullying, Swift made the smart move of re-recording all her albums to date, giving her ownership of the intellectual property and recording rights of her songs.

She has since broken many streaming and sales records, making her a billionaire as well as a pop culture icon. She has been involved in a number of philanthropic efforts, donating millions of dollars to food banks, flood relief efforts and children’s hospitals, as well as giving money to fans to help pay their medical or academic bills.

Is she a feminist? She might be. She is a woman who has made it to the top of her career and fought for control over the rights to her work while seemingly trying to help others with less fortune. More importantly, she can be. If we revisit the dictionary definition of feminism, this suggests Swift has at the very least, benefited from feminism. And within the feminist movement, which advocates for equal rights, there is space for all.

Or at least, there should be.

The Barbie row and tokenism

As an example of the strange turn of events of the 2020s, Barbie, once a symbol of oppressive beauty ideals, became public enemy number one among a group of people who found the film of the same name so objectionable they took to burning Barbie dolls on camera. “An alienating, dangerous, perverse film”, said one review, of the movie that satirises Barbie’s own history as well as patriarchal attitudes.

The film became the biggest hit of the year and one of the most successful of all time. Exposing so many people of different ages and from around the world to its “dangerous” message was clearly worrying for those who are distinctly opposed to the women’s rights movement. But why?

Feminism has been in the spotlight for the last decade or so, perhaps more than ever before thanks to social media. The #MeToo movement, which emerged in Hollywood when a few women began speaking up about their experiences of sexual assault and harrasment, soon spread to other countries and industries. Men suddenly found themselves in a changing world where they didn’t know what they could or could not say or do, and were confronted with the reality that many women have, at some point, felt pressured into having sex with them due to the historical power imbalance between genders.

Meanwhile the feminist movement has changed. The idea of individuals experiencing oppression in unique ways based on the combination of their race, class, gender identity and sexual orientation, otherwise known as intersectional feminism, is no longer a fringe concept. But just because these ideas entered mainstream consciousness, it doesn’t mean they are understood.

TV and films have more diverse casts than ever before. Compare most Hollywood rom-coms made circa 2000 to the productions of today and you’d be forgiven for thinking far more than two decades have past. This is a good thing.

In workplaces, companies began putting quotas in place to create more equitable workforces. This is also a good thing. But without a real understanding of what privilege is and what the root causes of discrimination are, this can do more harm than good. It leads to clumsy policies that upset the people who don’t get hired, who feel they are being passed over in favour of a trend for box-ticking. It is what leads to the cries of “feminism has gone too far,” and disheartening news like the recent poll suggesting that only 38% of US consumers consider feminism positive for society, while one-fifth (19%) believe it is negative.

This doesn’t mean we haven’t made a significant amount of progress (at least, in the Global North). When Christian Dior’s creative director sends models down the runway beneath signs about consent and unpaid caring responsibilities, you know that the wheels are turning somewhere. But a £600 T-shirt bearing the slogan “We should all be feminists” isn’t going to lift mothers out of poverty.

Girlboss feminism

When the first wave of feminism emerged in the late 19th century in western countries, its goal was to achieve basic rights such as voting, property rights and access to employment opportunities.

Skipping forward 150 years, a new theme appeared — that of women achieving success by becoming entrepreneurs, CEOs and leaders. The concept of ‘girlboss feminism’ gained popularity in the early 2010s thanks to a few key events: the publication of ‘#GIRLBOSS’ by businesswoman Sophia Amoruso, ‘Lean In’ by former Meta chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg, and of course, social media.

Both Amoruso and Sandberg worked hard to become two of the richest women in the world, no doubt inspiring to young girls who dream of careers and money and all the benefits attached. But here’s the sticking point — this particular strand of feminism prioritises individual success and wealth within the context of existing power structures, and fails to address the root of what causes gender inequality in the first place: poverty.

Consider trickle down economics for example, the theory that by increasing the wealth of the rich, they will spend more money which will trickle down throughout society, leading to more wealth for all. This is nonsense, otherwise we wouldn’t be in a scenario where the richest 1% of the world’s population gather two-thirds of all new wealth while global inequality has risen to the most extreme levels since the early 1900s. And we have irrefutable evidence that women globally are disproportionately impacted by poverty.

Audre Lord put this best: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” A more even balance of genders in leadership positions is commendable and necessary, but the pursuit of this type of success does not tackle the challenges faced globally by women of different races, economic backgrounds, with visible and invisible disabilities, and of different sexual orientations.

On “feminism has gone too far”

According to a recent survey carried out in 32 countries, around half of millennials and Gen Zers believe that society has gone too far in promoting the rights of women. Viewed with a glass half-full, this could suggest that younger generations have encountered less gender inequality in their lifetimes compared to their parents, for example. If we take a closer look at the countries in the report, with a few notable exceptions these are mostly wealthy nations where there may be greater employment and economic opportunities for women. However, at this very moment —

- Women in Yemen, Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan have no freedom of movement without being policed, forced to cover up or having a man escort them.

- Since 2022, abortion is banned in 14 US states.

- The impact of climate change in the Global South is disproportionately affecting women, with a direct link between increases in domestic violence and extreme weather events. A 2021 study showed how the economic stresses caused by flooding, drought or extreme heat in Kenya is exacerbating violence against women in their homes — rising by as much as 60% in the areas affected.

- Social media and online platforms, the most powerful forms of communication worldwide, are being used for gendered disinformation campaigns that particularly target women, girls and LGBTQ+ people.

- The latest report from the World Bank has found that not a single country in the world offers women the same opportunities as men in the workforce.

Meanwhile, we are sadly witnessing a huge backlash against the rights of trans and non-binary people, with the ideological right seizing on the opportunity to divide the feminist movement by weaponising women’s right to safety and a general misunderstanding of how to address things like public toilets, pronouns and language.

This is a very brief list of the state of women’s rights worldwide, from which one can only conclude that the pursuit of equal rights and opportunities for all (again, that dictionary terminology) still has a very, very long way to go. But it’s not impossible to get there.

What do women want in 2024?

There are many layered and intersecting issues that need to be addressed. Here is a list of a few of the things women want, and still don’t have:

- We want autonomy over our own bodies, with access to reproductive healthcare without fear of being criminalised.

- We want the freedom to be in public spaces without harassment.

- We want legislation that ensures femicide and all forms of non-consensual sex are crimes, and that police forces and other institutions with a remit to protect women do not employ violent abusers.

- We want a care income for the essential roles of raising children, caring for family members or other caring duties at home without which societies would not function, and that are placing millions of women worldwide into poverty and at risk of domestic violence because they lack economic freedom.

- We don’t want to have to pay a tax on products simply because they are designed for women (see the ‘pink tax’).

- We want women to be involved in making rules and policies that affect women’s economic, legal and human rights.

- We want policies that take into account the gendered impacts of the climate crisis.

- We want policies that protect women from being targeted by online harassment and gendered disinformation campaigns.

Last but not least, we need to have honest conversations about the fact that men also suffer because of the patriarchy and we must be more understanding of the shock of being confronted with the concept of privilege for the first time. As diversity and inclusion coach Farzana Nayani eloquently explained, “What we’re missing in society is how we take a step out of our own shoes into others’, to really see what the source of something is — is it pain, is it trauma, is it the need for safety? Why is that person so pro something and another so opposed? The values are actually the same, and when we really understand that, that’s when we can find the way forward.” This really is the only way we will ever bridge the barriers and achieve equal rights for everyone in our society.

READ MORE:

One thought on “What is feminism in 2024?”